Around this time in 2016, the predictions for the next year had reached something of a consensus: 2017 would be the year of augmented reality. But a funny thing happened on the way to the future — nothing much, really. At least not for the first half of the year.

It seemed clear that, after the success of Pokémon Go in the summer of 2016, the public was eager to begin seeing the world with new augmented reality eyes through their smartphones. But after all of the virtual monster frenzy died down, it turns out that Pokémon Go, while a strong signal of AR's potential, was, nevertheless, an outlier event. An entire year has now passed, and we have yet to see any new AR app remotely approach the levels of popularity of Niantic's hit.

So, is AR in trouble? As with all emerging technologies, the story is a bit more complicated than finding the next viral app.

2017 AR: Delayed on Arrival

In order for any new platform to take off, it needs the right vehicle. In the case of AR, at least in the short-term, that vehicle appears to be the iPhone. But half of the year had already expired before Apple took the stage at WWDC in June and revealed its ARKit tool for developers along with iOS 11. This mobile operating system update allowed users to participate in a more immersive form of AR using many of the iPhones already in our pockets.

Not long after, Google realized that the AR train was leaving the station without them, and quickly announced its own competing ARCore platform for Android phones. Combined these two developer platforms promise to reshape, at least virtually, the entire world around us through the screens of millions of smartphones around the world.

But first, developers have to build the AR apps and, so far, the going has been slow. Part of the issue in the case of ARKit is the fact that the public didn't get its hands on iOS 11 until September. Still, it's a bit surprising to find that there aren't more AR hits in the App Store. According to Apple CEO Tim Cook, as of a couple of months ago, there were already over 1,000 AR apps in the App Store. We can expect that number to grow every month in 2018 as developers try their hands at attracting AR app customers.

"We are seeing now with AR is that there is a real and tangible opportunity to reach more consumers," Tony Parisi, the head of VR and AR at Unity, told me just last week. "This is largely due to the fact that AR is no longer the future, it's available today and it will be available on more than 1 billion devices in the marketplace by the end of 2018."

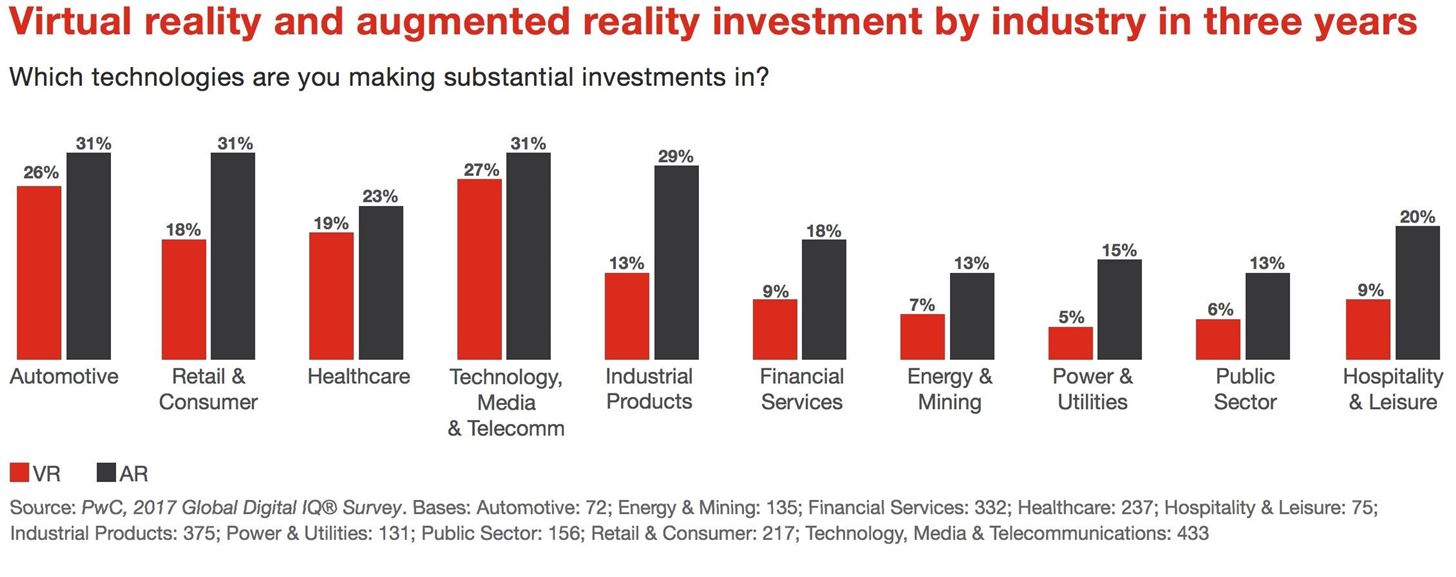

That growth is being fueled by increases in investment into augmented reality companies. According to a recent PwC report, AR investment is outpacing VR investment in every category, with the most dramatic differences being in the automotive, retail, and media/telecom categories. So while the most current immersive computing platform with the most pop culture traction is VR, with Hollywood regularly announcing VR deals, studios, and movie tie-in apps, it's clear that AR is where the long-term bets are being placed.

But aside from the logistics of getting the mobile AR toolkits into the hands of developers, and then seeding the consumer market with apps that go beyond furniture arrangements and virtual stickers, is the challenge of wrapping our collective minds around exactly what is and isn't possible with AR. It's not just another technology. Real, immersive AR comes with the prospect of transforming the entire world around us into interactive objects that can have real-world consequences.

This new AR paradigm requires a complete rethinking of computing interfaces. A new approach toward the relationship between the user and their device in real-world situations. For example, it's now possible to create an AR app that will use GPS to direct a person to walk into the middle of an intersection to take a selfie with a virtual celebrity they've been looking for all day that's part of some promotional Easter Egg hunt. What happens if that person does what many people are already doing — paying more attention to the screen on their smartphone while walking around in public instead of remaining aware of potentially dangerous obstacles around them? Hospital visits, or worse. That's just one of the many issues developers face as they attempt to create AR apps that aren't only engaging but responsible and practical.

- Don't Miss: Niantic & Warner Bros. Bringing Every Harry Potter Fan's Dream to Life with AR Game Based on Franchise

Other, unforeseen issues will likely arise in AR that we're just starting to imagine. For example, what if I geolocate a controversial or otherwise disruptive virtual statue in front of your store and take to social media and get thousands of people to visit it every week? What processes are in place to allow you, as a business or homeowner, to stop me from planting that AR statue there? A Pokémon Go Gym lawsuit gave us a hint, but it's still mostly unknown territory. Some of these AR cautionary tales and emerging best practices will begin to help the path forward come into focus in 2018 as more apps flood the market.

Smartphones vs. Glasses vs. The Future

On the upside, it's clear that investors are still bullish about AR, particularly in contrast to VR. That's likely because they understand something that's fairly obvious once you spend a decent amount of time analyzing both sectors: VR, as we know it today, is best suited as an escape experience (including interactive entertainment, passive consumption of visuals, and virtual meetings) in a stationary location. On the other hand, AR is limitless in its reach as a mobile-friendly tool for interfacing with the real world through our smartphones and tablets.

Those real-world AR interactions will begin to include everything from banking transactions, to driving and walking assistance (actually, some of this is already happening). Soon, AR will provide real-time language translations with subtitles floating over someone's head like captions during a foreign movie, but in the real world.

These AR scenarios are fascinating, but what is also rapidly becoming evident as we use more of these AR apps is that the AR dynamic is best suited to a wearable device, such as glasses, rather than a smartphone.

That's why there was so much early interest around Snapchat's Spectacles. Although the device served as a simple app-connected camera, it was also a kind of beta test to see just how interested users might be in interfacing with the world using a face-mounted device. The early results, as reported from Snap Inc. CEO Evan Spiegel, are not good. Only around 150,000 were sold and there are reportedly stacks of boxes of Spectacles sitting unwanted in Snap Inc.'s warehouses. That's not a great signal. But before we start any handwringing, we should remember that it's only one signal in a very nonspecific and only loosely-related-to-AR scenario. But what it means is that we still don't know if the public will flock to small, lightweight AR smartglasses as enthusiastically as they have smartphones.

And that's why everyone was so excited about Magic Leap.

For years the company has operated in stealth mode, with only the occasional bit of tantalizing news leaking out of major investments from heavyweights like Google and China's Alibaba Group, adding new wrinkles to its story. What we were led to believe is that Magic Leap represented a transformational new level of augmented reality, or as some like to call it, "mixed reality" (more on that later). In addition to the rumors of its visual and interactive innovation, the other rumors that followed Magic Leap suggested that the company could release a pair of AR glasses that look more like a pair of normal glasses than a head-mounted computer. But, according to Facebook's engineers, who weighed in on the topic at this year's Oculus Connect 4 conference, such technology is at least five years away.

It turns out Facebook was right.

With just a few weeks left in the year, Magic leap CEO Rony Abovitz finally took the wraps off of his secret device, the Magic Leap One: Creator Edition. Just slightly smaller than the HoloLens and Meta 2, the device suffered a few early shots for looking a lot like the space goggles worn by Vin Diesel in the Pitch Black sci-fi movie franchise. But it could still represent a major step forward for augmented reality visual hardware. That said, I have yet to hear anyone who isn't a tech insider (we'll wear anything) express any enthusiasm for walking around in public wearing Magic Leap's space goggles. But looks aside, let's first see if anyone actually gets to lay hands on the device before the end of 2018.

Cardboard AR

While high-end AR hardware incrementally crept toward a mainstream-friendly wearable form, other companies attempted to mimic the Google Cardboard strategy by giving people a cheap(er) placeholder AR headset to tide them over. The biggest such launch was the Lenovo Mirage, which so far only offers the Star Wars: Jedi Challenges experience. Other similar products included the Mira Prism, the Aryzon, and the developer-focused Holokit, the latter two of which are actually made of cardboard.

Like the VR-focused Google Cardboard and Samsung Gear VR, these products all require a smartphone to operate. However, unlike the Google Cardboard experience, which damaged VR's prospects with mainstream users by showing off a subpar VR experience, these smartphone-assisted AR devices are effective (albeit lower quality) glimpses at the higher-end AR experiences in development for more expensive devices.

In the coming months, we're likely to see a series of branded smartphone cradle AR devices, in much the same way that 2015 and 2016 saw everything from car companies to magazines releasing their own logo-emblazoned Google Cardboard-style devices for virtual reality. So far, other than the Star Wars-driven Lenovo Mirage, there's not much action in the smartphone cradle AR device space. Most people haven't heard of the Mira Prism, but HoloLens developer AfterNow just released a gaming app (see video below) for the device, called AlienWave, that offers an AR take on the classic Space Invaders game.

"From the trend we've seen in this second half of 2017, we can predict that AR Glasses projects in mid to large companies will increase sharply through 2018," AfterNow founder Philippe Lewicki told me in the waning days of December. "In the work place we'll have an improvement jump in AR glasses technology… from Magic Leap and other large players."

But will cheaper, smartphone cradle AR devices be enough to serve those waiting for easier to use, lower priced high-end AR headsets? The market will decide that in the coming months. For now, I take it as a slightly troubling signal that we've yet to see anyone present a hack of the very well designed Lenovo Mirage to show us something other than lightsaber battles and holochess. If there's major market for this mid-tier category between smartphone-based AR on the low end and the HoloLens on the high end, it hasn't made itself apparent, yet.

Mixed Up Reality

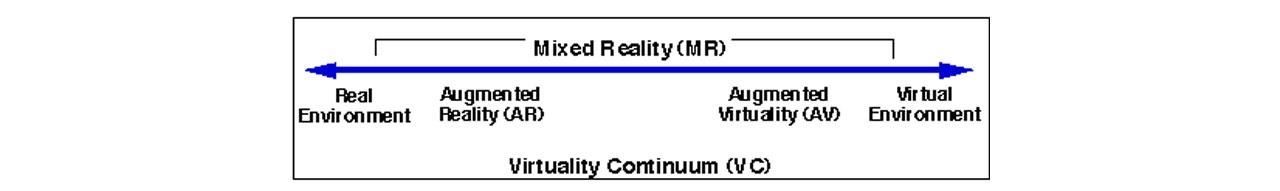

This all leads us to one of the other major trends of 2017: the rise in popularity of the term "mixed reality." This might be the most problematic tech term we've encountered in years. The idea being promoted by some is that, increasingly, the term "augmented reality" is no longer suitable since it supposedly only refers virtual images layered over the real world.

In contrast, mixed reality, according to its proponents, refers to virtual images that correspond to spatially mapped areas, allowing users to more directly interact with virtual objects that are responsive and convincingly positioned in the real world. (The definition tends to vary and shift depending on the person giving it.)

But this term adds an unnecessary layer of complication to a nascent space that already suffers from too many vaguely defined products and features, as immersive computing gradually finds its footing via various software tools and hardware implementations.

A research paper published back in 1994, titled "A Taxonomy of Mixed Reality Visual Displays," used "mixed reality" as a term that described "a particular subclass of VR related technologies that involve the merging of real and virtual worlds."

Even with visual aids, such as the chart below, the fine distinctions of what encompasses mixed reality may be lost on many consumers attempting to understand the term.

However, virtual reality pioneer Jaron Lanier, the person who coined the term "virtual reality" many years ago, recently gave a lecture in Seattle during which he shed some light on the mixed reality versus augmented reality debate.

"Mixed reality ... is probably better known as augmented reality ... people can argue, a lot of people think those terms mean different things and have distinctions to make, which is fine, but you can go crazy if you want to argue about these terms," said Lanier. (To hear it in context, fast forward to the 1:08:30 mark here.)

Let's repeat his thought: "a lot of people think those terms mean different things." The inference here is that the debate is nonsense.

I agree with Lanier.

If you feel the need to be puritanical and harken back to early research nomenclature, you'll refer to what is really just responsive/interactive AR as MR. But if you want "real" people to understand and, more importantly, confidently buy your products, you'll make the distinction clear and lean toward Lanier's use of the term augmented reality to refer to layering the real world with virtual objects. Adding the term "mixed reality" to the consumer fray has already caused confusion.

Question: What's in a mixed salad? Answer: Depends on the chef. What does it mean when your move to a new city is a "mixed bag"? Answer: Depends on the city. What does it mean when someone says the audience's reaction to a performance was "mixed"? Answer: The word "mixed" in this case means nothing without elaboration. Whether the topic is people, food, or tech, it's a word that is often mysterious by definition. Therefore, hanging the word "mixed" on your product means that you'll constantly be forced to explain what you mean by "mixed," because "mixed" could, for mainstream consumers, mean anything. Instead, you could just say that reality is being enhanced or (eureka!) augmented with virtual objects, both passive and active, spatially related to objects/structures in the real world and not.

(A suggestion for MR proponents: Perhaps limit the MR talk to technical lectures and insider discussions. If you want the public to embrace what's actually for sale "today," don't confuse them with fine line distinctions that won't be truly relevant until the holodeck era sometime in the next few decades.)

Let's be honest, and cease the baroque complications of tech conference cocktail talk: Today, what people are calling Mixed Reality is usually just meant to refer to "better" and "more immersive" Augmented Reality. Therefore, it's ok to just call it AR. There, fixed that for you.

Another reason the mixed reality tag is problematic is due to the efforts of Microsoft. The company has been marketing its virtual reality headsets as Windows Mixed Reality devices. But the vast majority of these devices aren't "mixed reality" devices, they are VR devices — full stop.

It's understandable that Microsoft would try to future-proof its products by branding the first versions of these VR headsets as mixed reality, with an eye toward a future when most of these devices can easily switch between VR and AR. I get it.

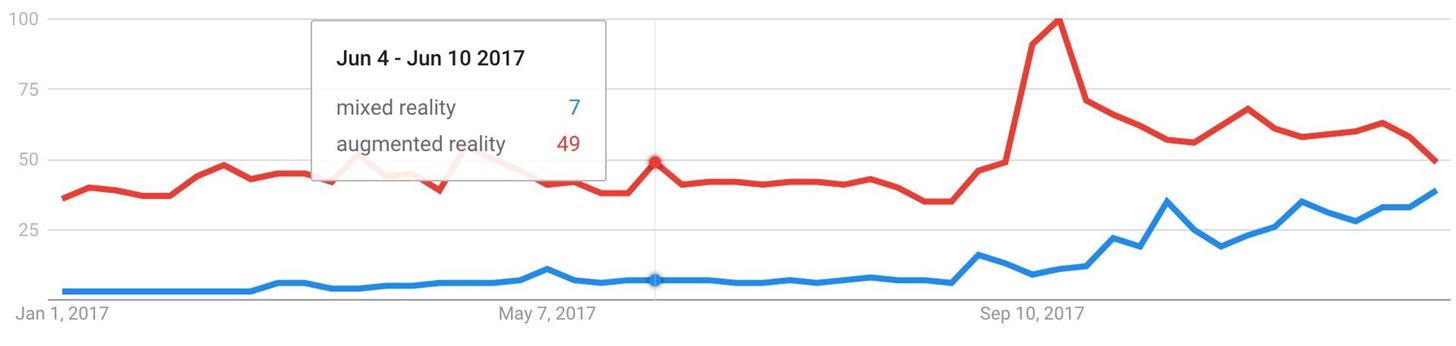

But right now, Microsoft's misnomer merely muddies the waters and confuses consumers in precisely the kind of way that will make it harder for everyone to translate what's actually on offer in the VR and AR spaces. As Google Trends shows, the number of people searching for the term "mixed reality" rose dramatically in 2017. That's not because mixed reality is suddenly the hot new thing (AR is), it's because Microsoft has a lot of marketing cash to push its branding.

Meanwhile, you have very smart people beginning to refer to more immersive AR as "MR," as though this subtle differentiation is absolutely necessary. It's not. And now I'm even beginning to see the term XR, or extended reality, slip into conversations, further confusing the non-tech-insider public.

- Don't Miss: 5 Major Problems Magic Leap One Faces on Day One

Here's another way to look at it:

Imagine the day, perhaps in five to 10 years, when haptics and sensory information related to temperature, moisture, etc. become common to all VR systems. Now imagine people start telling you that, no, you can't call that VR, because it's far more immersive. Instead, you must call "that" version of VR something like, oh, I don't know, IR (immersive reality). That sounds like just the kind of tech conference "well actually" terminology that might take hold in coming years. But it's silly. When that day comes, you can just call it "better" VR. No new initials needed.

So, everyone, please stop it. It's hard enough to get consumers to adopt new platforms without all the nomenclature nonsense. It's simple, for now, VR immerses you in an enclosed virtual environment, AR brings virtual objects (both passive and interactive) to the real world. Augmented reality is the thing, and "mixed reality" is just another unnecessary term being used to describe a better version of it.

Coming in 2018 ...

AR didn't explode in 2017, but it did become a lot more normal to mainstream users through Snapchat, Facebook, retail promotions, and iOS. These advancements have led to a rush of AR apps and devices seeding a market that is rapidly becoming ripe for a breakout hit.

Now let's see if 2018 can deliver the kind AR explosion so many were expecting in 2017.

Just updated your iPhone? You'll find new features for Podcasts, News, Books, and TV, as well as important security improvements and fresh wallpapers. Find out what's new and changed on your iPhone with the iOS 17.5 update.

1 Comment

Thanks for the observations and thoughts.

Regarding the term 'Mixed Reality' I totally agree. In our talks to different stakeholders we also perceived a lot of confusion around this term. We will rethink the application of this term to make communication easier - not only for consumers but also for professionals and b2b talk.

AR vs. VR - both have their use cases, already today. My guess is that both will evolve over time with the software parallel, because the software needed to manage the 3D content can in its core be the same for AR and VR. Therefor, it is not a race where only the one or the other thing will win. The user will less and less care about the device, but much more about his personal relevant content in a certain context and goes further towards ubiquitous computing: many-people-using-one-device, one-person-using-one-device, one-person-using-many-devices (incl. AR or VR or Mobile or Desktop etc.).

Share Your Thoughts